As a nation oppressed and shackled to English rule and tyranny for generations, the people of Ireland have historically joined hands with those suffering a similar fate around the world, especially Native Americans and the enslaved African American people.

It is this network of support and inspiration that led a young escaped black slave from the East Coast of America to Irish shores. A journey that motivated this brave man to become one of the most influential figures in the fight for the abolition of slavery.

Frederick Douglass became an author of his trials and tribulations, a motivational public speaker and leader of the Abolitionist Movement, but life began in more humble and harsh roots and with a different name.

Born into Slavery

In 1818, an enslaved woman called Harriet Bailey gave birth to a son, Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey. His father was never officially named, but was believed to have been the master of Holme Hill Farm, Talbot County, Maryland.

The infant was taken from his mother and she was transferred to another location. Frederick barely saw his mother again and was raised by his grandmother until he was sent to work as a slave as a boy of just seven years of age.

As easily as handing off a baked apple pie or a used book, Frederick was “given” to Lucretia Auld. Her husband Thomas, in turn sent the young boy to work for his brother Hugh and sister-in-law Sophia in Baltimore.

Sophia felt for the boy and gave into his instance on education by teaching him the alphabet. Frederick then took it upon himself to show his fellow captives how to read and write by using the Bible as a teaching aid. Word spread that slaves were being educated and Hugh’s brother Thomas was outraged that the Auld family were at the centre of gossip.

As punishment, Frederick was delivered to a most wicked master, Edward Covey. Edward was notorious for whipping and beating the slaves within his domain, his intention to break their hearts and minds, while leaving the bodies just damaged enough that they could continue to toil.

First Step to Freedom

Frederick made several attempts to escape, each time bringing down more wrath on the defiant young man. During his time working at a nearby shipyard, he befriended and began to fall in love with Anne Murray, a free woman. This spurred him onto a successful bid for freedom and he travelled to New York City with the help of abolitionist David Ruggles, while taking a great risk, as part of his journey took him through the enslaved state of Delaware.

Once in New York, Frederick and Ann were married and looking to start a family of their own, however Frederick was still an escaped slave, so they moved to the free state of Massachusetts and Frederick began to take his steps towards becoming a free man.

One of these steps was a change of name. Friends of the couple were fans of Scottish author and poet, Sir Walter Scott and suggested he change his surname name to that of the main characters of his poem, ‘The Lady of the Lake.’

His relationship with David Ruggles progressed and Frederick subscribed to ‘The Liberator,’ an abolitionist newspaper run by William Lloyd Garrison and Isaac Knapp. From here Frederick Douglass began attending meetings and then spent six months travelling through America as a public speaker , during which time he was repeatedly assaulted in the streets.

It was at this point, William Lloyd Garrison encouraged Frederick to visit Britain and Ireland to raise much needed funds and awareness for the movement.

Ireland’s Call

As Frederick made plans to travel, he had also completed writing his memoirs. His Irish friend, a printer in Dublin called Richard Webb, agreed to publish the autobiography.

Still an escaped slave, Frederick boarded an ocean liner in Boston with a first class ticket that had been purchased for him. The black man was forced into steerage as he did not have the ‘right’ to enjoy First Class. Douglass disembarked in Liverpool before continuing his journey to Dublin.

As Frederick set foot onto the Emerald Isle, the country under English Rule was at the beginning of what was to be one of the worst periods of Irish history – The Great Hunger, also known traditionally, as The Irish Potato Famine.

Despite their own suffering and fear, the people of Ireland welcomed Frederick Douglass with open arms and he put the wheels in motion with Richard Webb to print copies of his autobiography for sale at sold out lectures in Dublin, Cork, Limerick and Belfast. The book was selling faster than it could be printed, such was the impact the 27 year old African American was having on the oppressed nation.

The Liberator – Daniel O’Connell

It was however, the impact of Irishman Daniel O’Connell, who coincidentally became known as ‘The Liberator’ and who was a staunch supporter of the Abolitionist Movement.

On 29 September 1845, Irish Nationalist Daniel O’Connell took to the stage at a meeting of the Repeal Movement at Conciliation Hall in Dublin, inspiring Frederick Douglass to new levels of determination.

“I have been assailed for attacking the American institution, as it is called, negro slavery. I am not ashamed of that attack. I do not shrink from it. I am the advocate of civil and religious liberty all over the globe, and wherever tyranny exists, I am the foe of the tyrant.” – Daniel O’Connell

Spurred on by his time in the company of the Irish Nationalist, while in Belfast, Frederick Douglass wrote from his room at the Victoria Hotel to his friend William Lloyd Garrison on 1st January 1846 after four months touring Ireland.

Frederick Douglass

Victoria Hotel, Belfast,

January 1, 1846

To William Lloyd Garrison

My Dear Friend Garrison:

- I am now about to take leave of the Emerald Isle, for Glasgow, Scotland. I have been here a little more than four months. Up to this time, I have given no direct expression of the views, feelings and opinions which I have formed, respecting the character and condition of the people in this land. I have refrained thus purposely. I wish to speak advisedly, and in order to do this, I have waited till I trust experience has brought my opinions to an intelligent maturity. I have been thus careful, not because I think what I may say will have much effect in shaping the opinions of the world, but because whatever of influence I may possess, whether little or much, I wish it to go in the right direction, and according to truth. I hardly need say that, in speaking of Ireland, I shall be influenced by prejudices in favor of America. I think my circumstances all forbid that. I have no end to serve, no creed to uphold, no government to defend; and as to nation, I belong to none. I have no protection at home, or resting-place abroad. The land of my birth welcomes me to her shores only as a slave, and spurns with contempt the idea of treating me differently. So that I am an outcast from the society of my childhood, and an outlaw in the land of my birth. “I am a stranger with thee, and a sojourner as all my fathers were.” That men should be patriotic is to me perfectly natural; and as a philosophical fact, I am able to give it an intellectual recognition. But no further can I go. If ever I had any patriotism, or any capacity for the feeling, it was whips out of me long since by the lash of the American soul-drivers.

- In thinking of America, I sometimes find myself admiring her bright blue sky—her grand old woods—her fertile fields—her beautiful rivers— her mighty lakes, and star-crowned mountains. But my rapture is soon checked, my joy is soon turned to mourning. When I remember that all is cursed with the infernal spirit of slaveholding, robbery and wrong,— when I remember that with the waters of her noblest rivers, the tears of my brethren are borne to the ocean, disregarded and forgotten, and that her most fertile fields drink daily of the warm blood of my outraged sisters, I am filled with unutterable loathing, and led to reproach myself that any thing could fall from my lips in praise of such a land. America will not allow her children to love her. She seems bent on compelling those who would be her warmest friends, to be her worst enemies. May God give her repentance before it is too late, is the ardent prayer of my heart. I will continue to pray, labor and wait, believing that she cannot always be insensible to the dictates of justice, or deaf to the voice of humanity.

- My opportunities for learning the character and condition of the people of this land have been very great. I have travelled almost from the hill of “Howth” to the Giant’s Causeway, and from the Giant’s Causeway to Cape Clear. During these travels, I have met with much in the character and condition of the people to approve, and much to condemn—much that has thrilled me with pleasure—and very much that has filled me with pain. I will not, in this letter, attempt to give any description of those scenes which have given me pain. This I will do hereafter. I have enough, and more than your subscribers will be disposed to read at one time, of the bright side of the picture. I can truly say, I have spent some of the happiest moments of my life since landing in this country. I seem to have undergone a transformation. I live a new life. The warm and generous co-operation extended to me by the friends of my despised race—the prompt and liberal manner with which the press has rendered me its aid—the glorious enthusiasm with which thousands have flocked to hear the cruel wrongs of my down-trodden and longenslaved fellow-countrymen portrayed—the deep sympathy for the slave, and the strong abhorrence of the slaveholder, everywhere evinced—the cordiality with which members and ministers of various religious bodies, and of various shades of religious opinion, have embraced me, and lent me their aid—the kind hospitality constantly proffered to me by persons of the highest rank in society—the spirit of freedom that seems to animate all with whom I come in contact—and the entire absence of every thing that looked like prejudice against me, on account of the color of my skin—contrasted so strongly with my long and bitter experience in the United States, that I look with wonder and amazement on the transition. In the Southern part of the United States, I was a slave, thought of and spoken of as property. In the language of the LAW, “held, taken, reputed and adjudged to be a chattel in the hands of my owners and possessors, and their executors, administrators, and assigns, to all intents, constructions, and purposes whatsoever.”—Brev. Digest, 224. In the Northern States, a fugitive slave, liable to be hunted at any moment like a felon, and to be hurled into the terrible jaws of slavery— doomed by an inveterate prejudice against color to insult and outrage on every hand, (Massachusetts out of the question)—denied the privileges and courtesies common to others in the use of the most humble means of conveyance—shut out from the cabins on steamboats—refused admission to respectable hotels—caricatured, scorned, scoffed, mocked and maltreated with impunity by any one, (no matter how black his heart,) so he has a white skin. But now behold the change! Eleven days and a half gone, and I have crossed three thousand miles of the perilous deep. Instead of a democratic government, I am under a monarchical government. Instead of the bright blue sky of America, I am covered with the soft grey fog of the Emerald Isle. I breathe, and lo! the chattel becomes a man. I gaze around in vain for one who will question my equal humanity, claim me as his slave, or offer me an insult. I employ a cab—I am seated beside white people—I reach the hotel—I enter the same door— I am shown into the same parlor—I dine at the same table—and no one is offended. No delicate nose grows deformed in my presence. I find no difficulty here in obtaining admission into any place of worship, instruction or amusement, on equal terms with people as white as any I ever saw in the United States. I meet nothing to remind me of my complexion. I find myself regarded and treated at every turn with the kindness and deference paid to white people. When I go to church, I am met by no upturned nose and scornful lip to tell me, “We don’t allow n——s in here”!

- I remember, about two years ago, there was in Boston, near the south-west corner of Boston Common, a menagerie. I had long desired to see such a collection as I understood were being exhibited there. Never having had an opportunity while a slave, I resolved to seize this, my first, since my escape. I went, and as I approached the entrance to gain admission, I was met and told by the door-keeper, in a harsh and contemptuous tone, “We don’t allow n——rs in here.” I also remember attending a revival meeting in the Rev. Henry Jackson’s meeting-house, at New-Bedford, and going up the broad aisle to find a seat. I was met by a good deacon, who told me, in a pious tone, “We don’t allow n——s in here”! Soon after my arrival in New-Bedford from the South, I had a strong desire to attend the Lyceum, but was told, “We don’t allow n——s in here”! While passing from New York to Boston on the steamer Massachusetts, on the night of 9th Dec. 1843, when chilled almost through with the cold, I went into the cabin to get a little warm. I was soon touched upon the shoulder, and told, “We don’t allow n——s in here”! On arriving in Boston from an anti-slavery tour, hungry and tired, I went into an eating-house near my friend Mr. Campbell’s, to get some refreshments. I was met by a lad in a white apron, “We don’t allow n——s in here”! A week or two before leaving the United States, I had a meeting ape pointed at Weymouth, the home of that glorious band of true abolitionists, the Weston family, and others. On attempting to take a seat in the Omnibus to that place, I was told by the driver, (and I never shall forget his fiendish hate,) “I don’t allow n——rs in here”! Thank heaven for the respite I now enjoy! I had been in Dublin but a few days, when a gentleman of great respectability kindly offered to conduct me through all the public buildings of that beautiful city; and a little afterwards, I found myself dining with the Lord Mayor of Dublin. What a pity there was not some American democratic Christian at the door of his splendid mansion, to bark out at my approach, “They don’t allow n s in here”! The truth is, the people here know nothing of the republican Negro hate prevalent in our glorious land. They measure and esteem men according to their moral and intellectual worth, and not according to the color of their skin. Whatever may be said of the aristocracies here, there is none based on the color of a man’s skin. This species of aristocracy belongs pre-eminently to “the land of the free, and the home of the brave.” I have never found it abroad, in any but Americans. It sticks to them wherever they go. They find it almost as hard to get rid of it as to get rid of their skins.

- The second day after my arrival at Liverpool, in company with my friend Buffum, and several other friends, I went to Eaton Hall, the residence of the Marquis of Westminster, one of the most splendid buildings in England. On approaching the door, I found several of our American passengers, who came out with us in the Cambria, waiting at the door for admission, as but one party was allowed in the house at a time. We all had to wait till the company within came out. And of all the faces, expressive of chagrin, those of the Americans were pre-eminent. They looked as sour as vinegar, and bitter as gall, when they found I was to be admitted on equal terms with themselves. When the door was opened, I walked in, on an equal footing with my white fellow-citizens, and from all I could see, I had as much attention paid me by the servants that showed us through the house, as any with a paler skin. As I walked through the building, the statuary did not fall down, the pictures did not leap from their places, the doors did not refuse to open, and the servants did not say, “We don’t allow n——s in here”!

- A happy new year to you, and all the friends of freedom.

- Excuse this imperfect scrawl, and believe me to be ever and always yours,

Frederick Douglass

Sailing to Freedom

From the beauty of Howth to the wonder of the Giant’s Causeway, from Cork and Father Theobald Matthew and to Dublin and Daniel O’Connell, the people of Ireland showed Frederick Douglass wonder, warmth and inspiration, not hunger, death and oppression. He became known as ‘The Black O’Connell’, a camaraderie founded on persecution between the two inspirational speakers.

From here, Frederick sailed for Scotland and Glasgow where he continued to speak to gain support for the Abolitionist Movement.

Early in 1846, Frederick Douglass sailed the Atlantic Ocean with the money from his tour and book sales. When he stood back on the terra nova of the land of the brave and the home of the free, he took that money and bought his own freedom.

The life and times of Frederick Douglass continued for many more years, his commitment to freeing slaves and pushing for the abolition of slavery was unyielding. His dream was realised in 1865 when he was 47 years old, with the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution.

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born a slave in 1818. Frederick Douglass died in 1891, a free man. Let us not forget that some 46 years previously, this man of great strength and determination lived the life of a free man in oppressed Ireland.

“Instead of the bright blue sky of America, I am covered with the soft grey fog of the Emerald Isle. I breath and lo! The chattel becomes a man.”

References: RTE Archives, History Channel, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, University at Buffalo, Yale University.

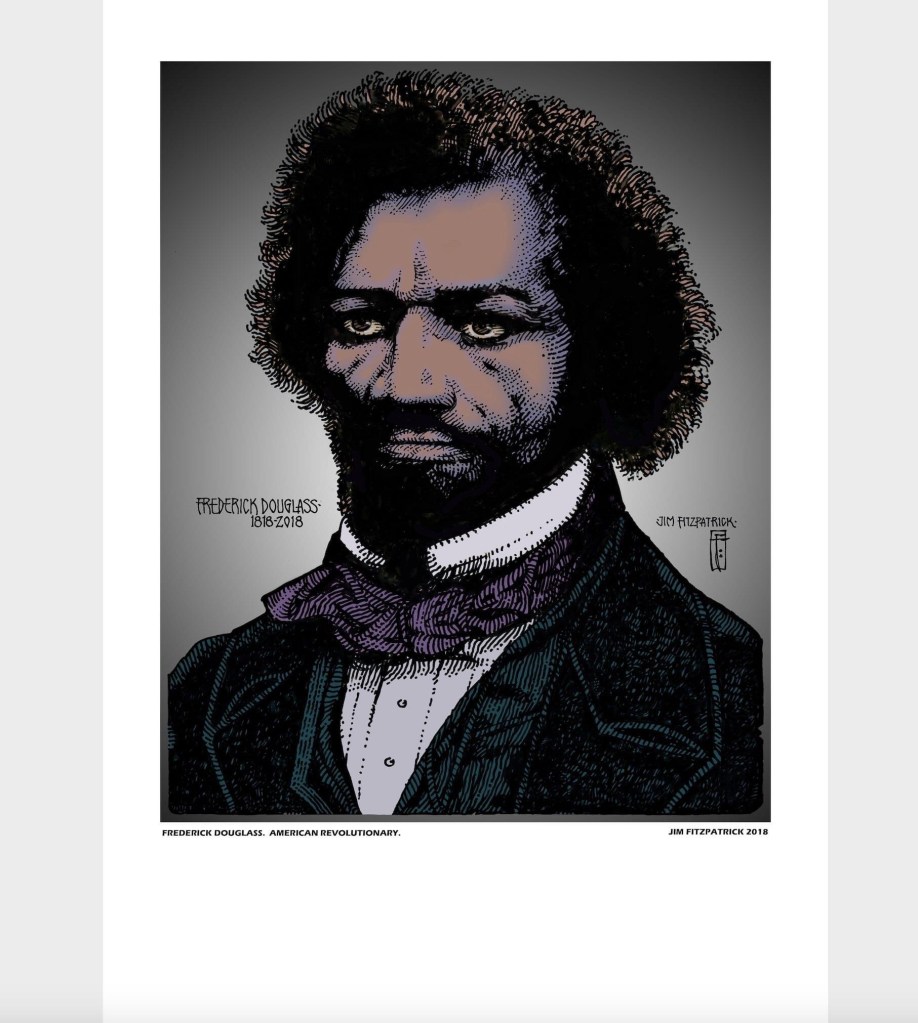

Artwork reproduced with the kind permission of Jim Fitzpatrick.